A blank page is both a challenge and invitation.

Blank Page is a podcast & a blog. Both? Yes, both. It includes original articles that I present as podcast episodes, and guest articles written by diverse people that I interview for the podcast. You can read the article, listen to the article and the interviews about the article, read the article first and then listen to the interview, or any other combination that makes sense for you. It’s a blank page; make what you want out of it.

Topics Include: Faith & Religion, Nonprofits & Fundraising, Fiction & Original Stories, Creative Writing & Storytelling, Neurodiversity & Life with AutismWhy Stories Matter with Jim Hodnett.

You won’t want to miss my conversation with Jim Hodnett, where we discuss the power of storytelling in fostering empathy, confronting fear, and pushing back against book bans. Jim’s article, Why Stories Matter, dives deep into his personal journey, the importance of representation, and the alarming rise in book censorship. He highlights how stories can shape understanding, empower marginalized voices, and challenge systems of oppression.

Listen to our interview and read his full article below.

You won’t want to miss my conversation with Jim Hodnett, where we discuss the power of storytelling in fostering empathy, confronting fear, and pushing back against book bans. Jim’s article, Why Stories Matter, dives deep into his personal journey, the importance of representation, and the alarming rise in book censorship. He highlights how stories can shape understanding, empower marginalized voices, and challenge systems of oppression.

Why Stories Matter. Fostering Empathy, Fighting Fear, and Challenging Book Bans.

by Jim Hodnett

Background: Why a Book about Banned Topics?

I’m a gay man, but it took a long time for me to come to terms with that fact. I grew up in the 1950s and ‘60s in a small city in Arkansas; I had no access to any information about gay people. I knew no one who was out—at least to me–and never saw a book on the topic. If the subject was mentioned at all in the Southern Baptist church that my family attended, it was likely spoken in the same breath as the word abomination. So, I had no way of classifying or understanding my feelings toward other boys. I thought I was the only person in the world who felt the way I did. I tried to recast my crushes on boys as mere hero worship of guys who were more confident or athletic or socially skilled than I was.

The only impression I remember having gained about homosexual men was very negative—that they were effeminate, repulsive, and laughable. So I worked hard to conceal any feminine traits I possessed and to conceal my feelings about other boys, even from myself. I did not come to understand myself as gay until I was twenty. I was appalled by the realization I stayed in the closet until my late 20s and did not fully come out until my mid-30s.

The dearth of information about gay people during my young and impressionable years quite obviously did not make me straight, nor even less gay. It only served to make me isolated, depressed, anxious, and prone to suicidal ideation. I do not want any young person of any gender or sexual orientation ever to have to go through the kind of childhood and adolescence I endured. They deserve to know the truth about who they are, that they are not alone and not sick, and can live happy, fulfilled lives. This is one of many reasons I pitched the Ohio Writers’ Association’s newest anthology, Should this Book Be Banned?.

Should this Book Be Banned? is a collection of short stories and other creative nonfiction that the Ohio Writers Association is publishing this spring. It contains nuanced portrayals of people, cultures, and topics that many people would like to see banished from the public consciousness, at least from a positive or affirming perspective. We know this to be true because the idea for Should this Book Be Banned? stemmed from the alarming rate of book bans in the U.S. in the last few years. According to PEN America and the American Library Association, there have been thousands of attempts (most successful) to ban books in school and public libraries since 2021. PEN America states that since July 2021, they have recorded 15,940 instances of book bans across 43 states and 415 public school districts. Forty-four percent of the banned books were about people or characters of color, and 39% were about LGBTQ+ people and characters. Fifty-seven percent of the banned books had sexual themes or content. Most of the banned books (60%) were written for a young adult audience and often depicted issues and situations that adolescents deal with: grief and death, substance abuse, suicide, sexual violence, depression and other mental health concerns.

In addition, several state legislatures have passed or proposed bills banning the teaching of the"1619 Project," a research and historical endeavor that views American history through the lens of the lasting effects of slavery and the pervasive and systemic nature of racism. In 2023, the Florida State Board of Education added a guideline that the teaching of African American history must include the assertion that “slavery benefited some enslaved people because it taught them useful skills.” This is one of those statements that contains a tiny kernel of truth but colossally misses the point. In Texas high school history books, students learn that the output of the Harlem Renaissance was inferior to other art of the era. Taken together, these bans on books and ideas have the feel of an attempt to erase (in some cases, literally "whitewash") the lives, culture, history, and legitimacy of people in historically marginalized groups in America. It outrages me.

Why Stories Matter

Numerous studies have shown that people who read fiction, particularly literary fiction, tend to exhibit more empathy toward others, especially others in stigmatized groups. (Check out the Aug. 28, 2020, issue of Discover magazine for more information.) When we read fiction, we enter the lives of the characters in the stories and learn what makes them tick, what their challenges and struggles are, and how they view the world. When readers are members of one or more privileged groups, they can understand how those who are marginalized view them and what they can do to foster equity. And, of course, if you are a member of a marginalized group and are reading about others like you, just as I said above, you feel less isolated and more empowered. You can shed more easily the internalized racism or internalized homophobia or whatever other self-loathing attitudes you may have picked up over the years. Authentic, honest stories written by and about marginalized communities have the power to save lives.

But book bans are an attempt to control the narrative, to impose a particular viewpoint favorable to the ruling class on everyone else. As Winston Churchill said, “History is written by the victors.” Book bans come from a place of fear on the part of the victors, fear that their position of privilege will be taken from them.

Isabel Wilkinson, who wrote Caste, The Origins of Our Discontents, said that it is not true that people who vote for Trump are voting against their own interests (although I would argue that they actually are doing that in the economic sense because his policies will widen the gap between the rich and poor and reduce social supports). But most Trump voters believe a vote for him will preserve their privilege—the privileges they enjoy based on being in the dominant race or religion or sexual orientation or gender or on the basis of speaking the dominant language. And they are right. Preserving white male Christian supremacy, etc., is a cornerstone of Trump’s agenda: closing the border, deporting immigrants, abolishing DEI trainings and initiatives, denying gender-affirming medical care, banning abortions, banning Muslims, and on and on.

I think all those things are based on fear of the other.

I don’t have any illusions that Should This Book Be Banned? is going to turn around the tide of hatred and fear in our country or turn the zeitgeist away from preservation of privilege and toward equity and equality of opportunity—at least not in any enormous way. But I think every pushback has some effect. Bayard Rustin, the African American gay man who organized the 1963 March on Washington for civil rights, told us all to “speak truth to power” because when we do, we give people who are marginalized something to hang onto, something to help them feel more empowered and proud.

What I hope is that someone will pick up Should This Book Be Banned? and see themselves portrayed positively in it and thus feel less alone. I also hope someone will pick it up and see people they know in it, perhaps a family member or neighbor, and understand what that person faces every day just by trying to be true to themselves.

I once heard it said that coming out is an act of survival. The more people who know they have an LGBTQ+ family member, neighbor, co-worker, or friend, the more we are seen in the fullness of our humanity, and thus, the less scary we are. The same goes for any other marginalized group. The more visible they and their humanity and gifts are, the less likely they are to be seen as a threat.

For writers and creators from marginalized communities, I say to keep speaking your truth to power. Your truth doesn’t have to be a blatant political truth. You don’t have to be polemical. Your truth can just be something like, This is what it is like to walk around in a black body, or a gay body, or a fat body, or a female body or a trans body.

Whatever approach you take, stand your ground. The Civil Rights heroes of the 1950s and 60s showed us how. And stay connected to and united with other marginalized groups. If the rights of one group are diminished, all are imperiled. People in power, the decision-makers, need to know that we have always been here, we are not going away, and we will not be silent.

Tell Better Stories

Growing up, I could never figure out what I wanted to be.

I could honestly imagine myself as a lawyer, bartender, gas station attendant, pilot, pastor, or something else entirely. With each job, there was something that intrigued me! I could imagine myself going to work every day to sell people gas and cigarettes. It would be fascinating! Whenever I watch a movie about a lawyer, I think, “I could do that.” In college, I planned to be a pilot until I found flying small planes made me want to throw up.

With time, I learned that what intrigued me about these positions had little to do with what I should do with my life and more to do with my love of stories. I’m fascinated with these professions like an author is fascinated by their characters’ lives. Even the most boring of characters—or the most evil—are deeply loved by their authors. If they aren’t, the character will fall flat. Good characters are loved with a courageous curiosity. Authors want to know what makes them get out of bed every day. What do they worry about? What are they most afraid of? Why do they do what they do? These questions are at the heart of great stories and I love great stories.

If the story is good, you’ll forget where you are, about the laundry you need to do, or that your feet are sticking to the floor of the theater.

Stories transport us.

Storytelling is one of the few human traits that is truly universal through all of culture and known history.

We had stories before we had IMAX theaters and novels.

We had stories before we had paper to write them down.

It’s what makes us human. Apes might have opposable thumbs and be able to use tools, but humans alone have the gift of storytelling.

We love comedians because they are actually some of the best storytellers out there.

We have an obsession with storytelling because, in all the changes we’ve seen in society, storytelling remains the most effective way to make sense of our world, cast a vision for new ideas, and provide comfort and distractions from the tediousness of life.

It’s because of this that telling better stories remains the most important thing you can do to improve your quality of life, connection with other humans, and effectiveness in nearly every corner of the job market.

Finding A Writing Community

I have the privilege of serving as the President of the Ohio Writers’ Association (OWA) since it transitioned from an LLC to a nonprofit. I’m not the best writer, by any stretch of the imagination, and I’ve only had a few fiction short stories published up to this point. That’s what I love about OWA. You don't have to be great to get involved. It’s more about what you will get out of it than what you’re expected to put into it. This community of writers continues to inspire and challenge me to be the best writer I can be.

Along with being a part of OWA, I serve as the pastor of Cityview Church. Most weeks, you’ll find me up front sharing a message. If I struggle to write as much fiction as I want, it’s because most weeks I’m writing 3000-4000 words in a sermon. When interacting with people outside the church, I’ll often say I spend a lot of time writing “creative nonfiction,” but that’s just my way of making sermons sound cooler than they are.

Whether as a writer, public speaker, or leader, I find knowing how to share stories is essential. This is true for a manager of staff or serving as a board member; every part of life and leadership requires stories, because stories are our primary way of connecting, relating, and making sense of our world.

In business and organizations, you might have a mission statement, but it’s stories that help people see what your mission looks like with clothes on. Whether it’s fundraising, volunteer recruitment, asking for help, or anything else, being able to craft a simple story that draws people in makes the difference between connecting with a potential audience and not.

Most of what I’m sharing here I’ve learned from other people, whether it be professional writers or peers offering advice in a monthly critique. I doubt I’ll be offering anything original, but I think the following tips and tricks represent some of the best practices I’ve learned for storytelling. For some, this might be brand new, and for many others, I hope this will be a helpful reminder.

While I use these principles for both writing, speaking, and leadership—whether I’m writing science fiction, preaching, or casting vision—it’s possible some tips might lend themselves to one form more than the other. Wherever you use storytelling, here are eight tips I’ve picked up that have helped me tell better stories…

…

You can continue reading on my eBook Tell Better Stories, a free gift to anyone who subscribes to my email list.

I'm getting published!

Guess what happened today? It's the moment I've been working towards for a couple years now.

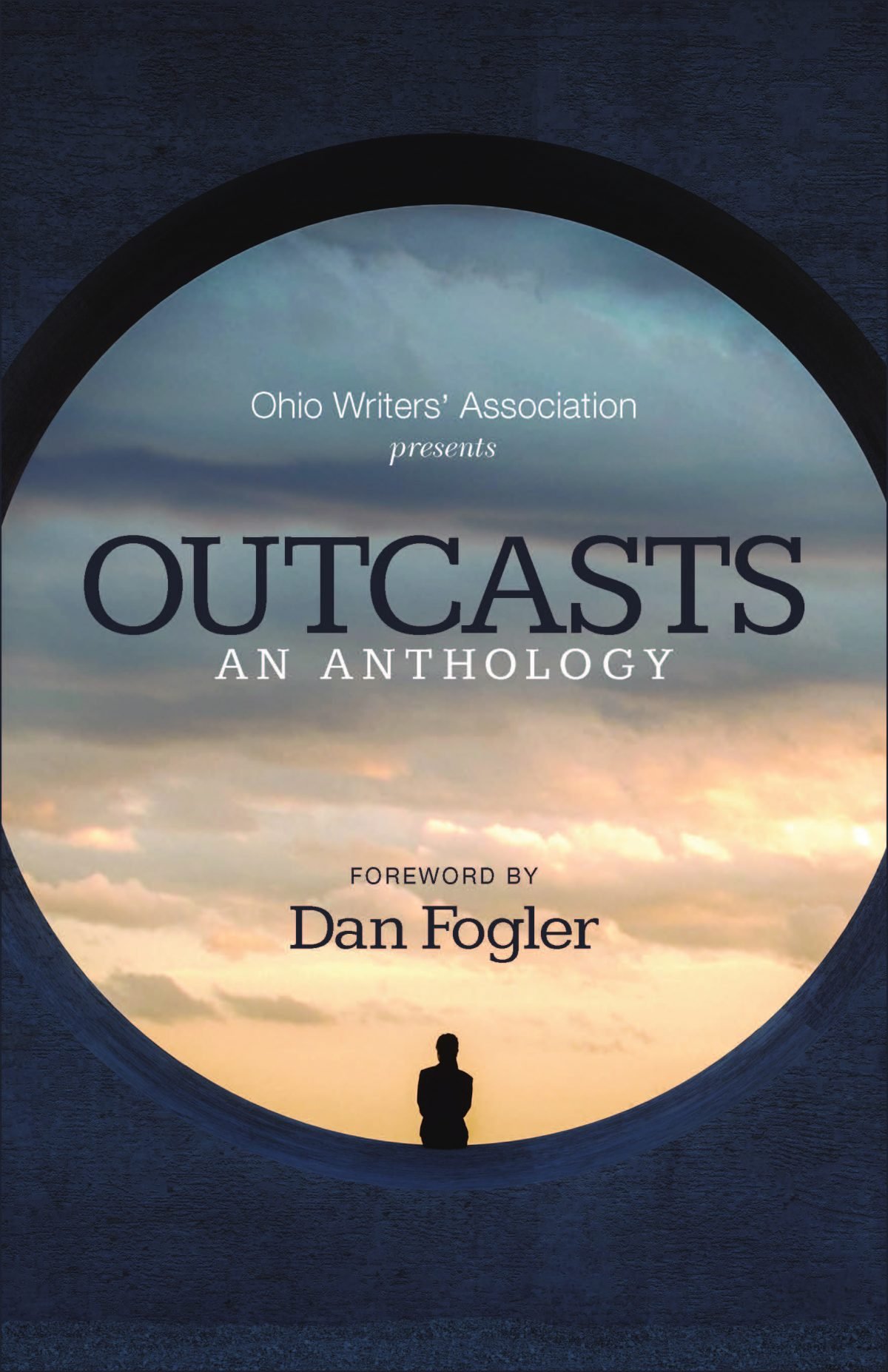

I'm excited to announce that my short story “The Priest and the Robot” has been included for publication in the Ohio Writer’s Association’s newest anthology, “Outcasts.”

This will be my first publication, so it warrants some kind of party, right?

I’m included alongside a number of amazing Ohio writers, including a few friends I've made recently in the Ohio Writer's monthly workshop. It's a fantastic group!

Oh, and this is fun: the anthology will include a forward by actor Dan Fogler, who is known for his acting in Fantastic Beasts and the TV series Walking Dead. I think I might get to meet him? So that's fun!

Check out the complete list of short stories here.

I've always considered myself a creative, who has dabbled in numerous art-forms, and lately I've considered myself a writer... but now that I'm getting published, does that make me an author? idk.

Either way, if you're willing, help me build my author page on Facebook by liking & following it here: https://www.facebook.com/joegravesauthor